Kernel Address Space Randomization in Linux or how I made Volatility bruteforce the page tables

This is part one of a three part series.

Recently I attended a memory forensics workshop where I refreshed my Volatility skills. When I returned my coworkers asked me to give a tutorial on how Volatility worked and explain the basics of computer forensics.

I was happy to oblige, planned a 3 session tutorial, created slides and planned to do some hands on after each presentation. For memory forensics on Windows systems I could reuse the training material from the workshop, but to also cover the Linux side of things I needed to create some memory dumps on my own.

Since Debian is the stock-disto at work and Debian Stretch is going to be released soon I made sure everything worked on the 4.7 kernel shipped with Stretch in December. The LiME DKMS built just fine, also creating a matching Volatility profile was trivial, and Volatility gladly (after resolving a minor issue) told me everything I wanted to know about the memory image.

Fast forward two weeks, just before the first tutorial was to take place: I installed a fresh Debian Stretch VM, took an image of the memory and created a new profile, since the linux-image-amd64 had just been upgraded to Linux 4.8. When I fired up Volatility to give me the process list all I got was No suitable address space mapping found. Damned.

I had a look at the open issues in the Volatility Github repository and the Debian maintainer of the Volatility package had similar problems, alas with kernels < 4.8.

At this point I want to summarize the research I did regarding the issue and give you a primer on amd64 memory address translation, Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), a Linux feature called Kernel Identity Paging and how Volatility validates profiles/address spaces when used with memory images acquired on Linux systems.

Address Translation on AMD64

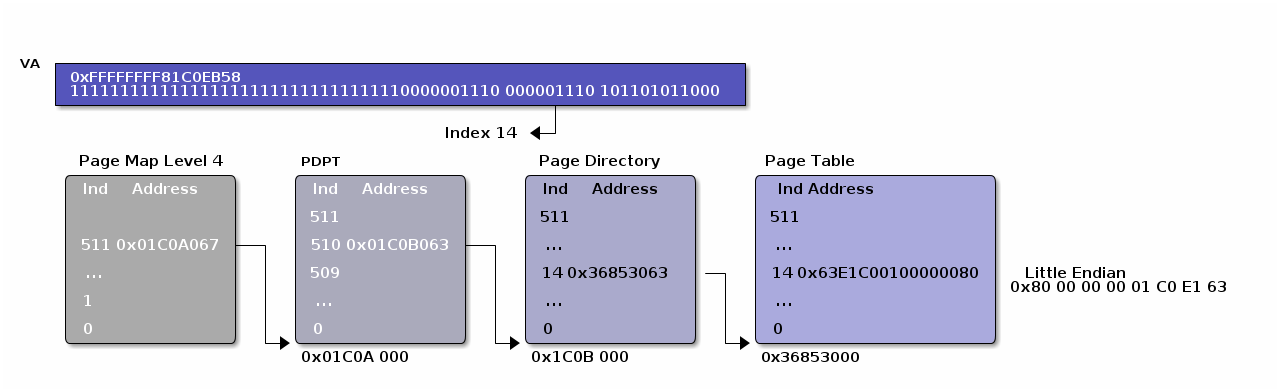

On modern platforms you have virtual addresses (VA) that can be translated to physical addresses (PA) in RAM by the Memory Management Unit (MMU). The input for the MMU is the value of the CPU register CR3 and a virtual address (also called linear address) which in case of amd64 is 64 bit long. From these 64 bits only 48 bit are relevant as of now but Linux kernel infrastucture is currently adapted to utilize all 64 bits. But I’ll only focus on the current 4 level paging MMUs for this topic.

The low 48 bits of the VA are split into multiple sections. The physical address of the page map is stored in CR3. The first section is used to determine the PA of the page map entry in combination with the value from CR3 (Volatility refers to it as DTB, the directory table base). The second section is used to determine the PA of the page directory pointer table (PDPT) entry in combination with the the value retrieved from the page map. The third section is used to determine the PA of the page directory (PD) entry in combination with the value retrieved from the PDPT. The forth section is used to determine the PA of the page table entry (PTE) in combination with the value retrieved from the PD. Finally the last section is used to calculate the offset within the page pointed to by the PTE.

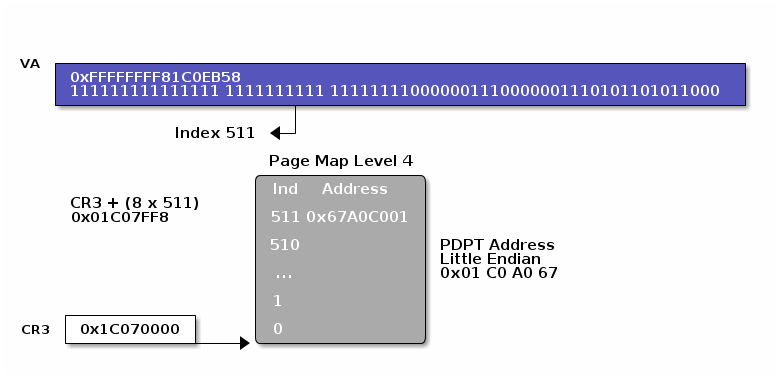

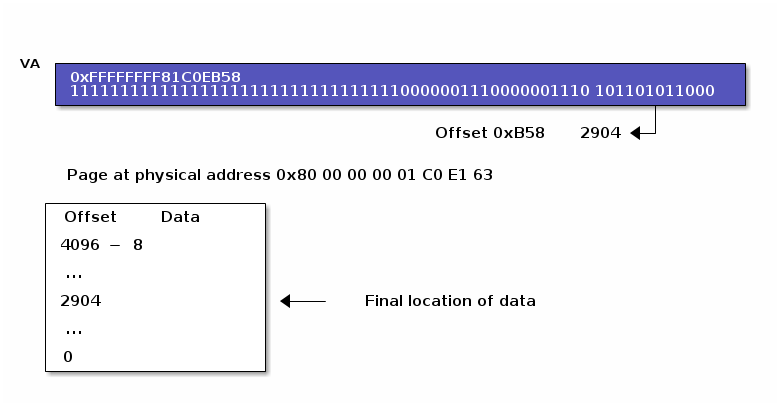

An example translation is illustrated for virtual address 0xFFFFFFFF81C0EB58. The DTB is 0x1C07000. Note that little endian order for entries in tables is used and that a binary translation is required.

CR3

This is a CPU register that contains a 64 bit value. Bits [51:12] point to the physical address of the page map. The value of CR3 is also called the Directory Table Base (DTB) and is individual for each process.

VA

0xFFFFFFFF81C0EB58 translated to binary is 1111111111111111111111111111111110000001110000001110101101011000

In each of the following translation steps different parts of this VA will be relevant.

Page Map Level 4/PGD

The page map is a structure in memory with a total size of 4096 bytes that contains 512 page map entries of 8 bytes each. Those page map entries contain physical addresses of page directory pointer tables. The relevant part for the page map entry in the virtual address are bits [47:39]. To calculate the physical address of a page map entry for a virtual address the following formula is applied: pa_pme = (CR3[51:12] & 0xFFFFFFFFFF000) | ((va & 0xFF8000000000)>> 36)

The 8 byte value at this physical address is the physical address of the PDPT base for the virtual address. So in our example the page map entry would be 0x1C07FF8:

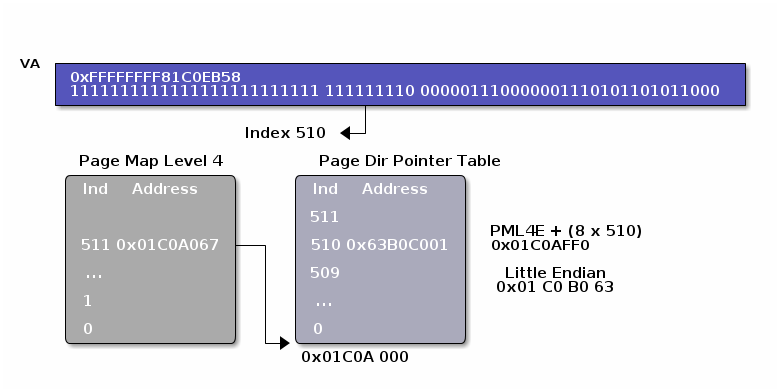

Page Directory Pointer Table/PUD

The PDPT also contains 512 8 byte values. To find the address of the

page directory that is relevant for the VA the entry

with offset of va[38:30] is read:

pa_pdpte = (pa_pme & 0xFFFFFFFFFF000 ) | ((va & 0x7FC0000000) >> 27)

Again, the value at that address points to the page directory base

for the virtual address.

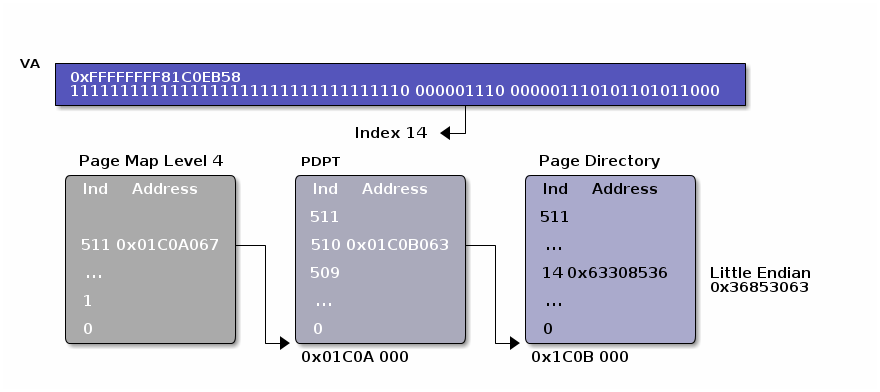

Page Directory/PMD

See above: 512 8 byte values.

To find the page table base:

pa_pde = (pa_pdpte & 0xFFFFFFFFFF000) | ((va >> 21) & (512 - 1)) * 8

Page Table/PT

Page

Within the page data is read starting from offset, where offset is va[11:0]

Address Space Layout Randomization

After the introduction of Non-Executable pages, exploits could no longer rely on injection of shell code into memory regions designated to hold only data to achieve arbitrary code execution. To work around this restriction, they could utilize return-oriented-programming, i.e. using already loaded executable sections and rearranging their order/parameters in a way that they still got what they wanted. When I was young, ROP was quite easy, since memory addresses for data and code segments of ELF binaries as well as their heap etc. where static. Thus if someone found a buffer overlow in your program, he would know which jump targets would be worthwile to redirect the program flow to. In order to mitigate this ASLR was invented (even though originally only as a short-lived temporary measure). When a binary is compiled with ASLR support the addresses where a certain function is located at run time can change each time the program is loaded. ASLR makes it more difficult to reliably exploit vulnerabilties in a way that doesn’t crash the application, since an attacker does no longer immediately know the addresses of the functions that he wants to return to, and thus a tampered instruction pointer might not point to a valid entry point of a function but somewhere else.

Why is this relevant here? Well, in kernel version 3.14 Linux introduced ASLR not only for user space applications but also for the kernel itself. So when booting, some entropy is generated and all the kernel symbols that were at a static locations before (as written down in the holy /boot/System.map) could now be almost anywhere in the virtual or physical address space. So the function for KASLR prior to kernel 4.8 was basically:

wait_for_enough entropy

r = calculate_random_number_from_entropy

kernel_symbols.each do |sym|

kernel_symbol_addresses[sym] = System.map[sym] + r

end

#=> KASRL enabled!So if an attacker wanted to utilize a VA in System.map to determine the location of a worthwile jump target he would not be able to do so trivially if he didn’t know r.

It is important to note that until 4.8 the same r was used for VA as well as for PA. This has something to do with kernel identity paging, which I’ll explain in a bit. Moreover the relative positions of various functions etc. defined in System.map don’t change, i.e.:

kernel_symbol_addresses[sym1] - kernel_symbol_addresses[sym2] == System.map[sym1] - System.map[sym2]Starting with kernel 4.8 KASLR will use separate random offsets for VA and for the PA, so if you are able to find out the random offset for PAs you do not automatically have the random offset for VAs. This is the part that bit me. More on this a little later.

Kernel Identity Paging

If you have two virtual addresses va1 and va2 and va1 - va2 = 0xFFFFFF and both are applied to the same DTB this does not mean that their corresponding physical addresses pa1 and pa2 are also 0xFFFFFF apart.

However for the virtual addresses in System.map describing kernel code and data this is the case. Moreover without KASLR the physical address of a symbol plus a known offset corresponds to the virtual address:

physical_address[sym1] + known_offset = System.map[sym1]

physical_address[sym2] + known_offset = System.map[sym2]This mechanism is leveraged by Volatility to validate the LinuxAMD64AddressSpace and in case of pre-4.8 KASLR to easily figure out the random offset.

Address Space Validation

In order to succesfully work on a memory image, Volatility requires a profile for the operating system from which the image was acquired. A profile consists of 2 files:

- The

System.mapfor the exact kernel version that was running when the imaging took place and - a

dwarffile containing the structure, sizes and member offsets for all kernel relevant data types, structs and so on in an easily parsable format.

The dwarf file lets Volatility for example figure out at which offset from the start of a process struct (task_struct) the PID or process name is stored.

As discussed before, a DTB is required to resolve virtual addresses to physical ones. To get a complete overview of the memory image, Volatility tries to determine the kernel DTB, aka the DTB of the process with PID 0. Once that DTB is determined all other processes and their DTBs can easily be figured out, since all processes are stored in a double linked list which can be traversed easily once you have an entry point.

Let’s have a look at the code that tries to find this DTB, when the kernel is not relocated/KASLRed:

# The symbol which should point to our DTB

sym = "init_level4_pgt"

# Possible values for the known_offsets

shifts = [0xffffffff80000000, 0xffffffff80000000 - 0x1000000, 0xffffffff7fe00000]

# The virtual address of the "init_task" symbol

init_task_addr = tbl["init_task"][0][0]

# The VA of the DTB symbol

dtb_sym_addr = tbl[sym][0][0]

# The offset of the process name in a task_struct

comm_offset = profile.get_obj_offset("task_struct", "comm")

# The offset of the PID in a task_struct

pid_offset = self.obj_vm.profile.get_obj_offset("task_struct", "pid")

# Iterate over all known_offset candidates

for shift in shifts:

sym_addr = dtb_sym_addr - shift

# Determine the PA where the process name of the initial task, "swapper" should be

read_addr = init_task_addr - shift + comm_offset

# Read from the PA

buf = pas.read(read_addr, 12)

if buf:

# Check if the expected name "swapper" shows up at the correct spot

idx = buf.find("swapper")

if idx == 0:

# If it does, we found the DTB

good_dtb = sym_addr

breakThis works quite well if KASLR or kernel relocation is not involved. In case this doesn’t work, Volatility searches for a needle in the haystack:

# Search for the string "swapper/0" followed

# by some null bytes in physical memory

scanner = swapperScan(needles = ["swapper/0\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"])

for swapper_offset in scanner.scan(self.obj_vm):

swapper_address = swapper_offset - comm_offset

# Check several conditions

if pas.read(swapper_address, 4) != "\x00\x00\x00\x00":

continue

if pas.read(swapper_address + pid_offset, 4) != "\x00\x00\x00\x00":

continue

# Determine the relocation/KASLR shift by subtracting the

# expected PA of "init_task" from the PA where the conditions

# above apply

tmp_shift_address = swapper_address - (init_task_addr - shifts[0])

if tmp_shift_address & 0xfff != 0x000:

continue

shift_address = tmp_shift_address

good_dtb = dtb_sym_addr - shifts[0] + shift_address

breakSo far so good. If Volatility succesfully found a DTB it will then try to validate its findings. If no KASLR shift was found it basically does this:

# Using the DTB found before and emulating a MMU

# calculate the PA for the VA of the symbol "init_task"

pa = translate_virtual_to_physical(init_task_addr)

# Validate kernel identity paging

for shift in shifts:

if pa == (init_task_addr - shift):

yield trueIf a KASLR shift was found it will add this shift accordingly, again validating that identity paging is in place.

If the identity paging check fails, the address space is considered invalid.

Back to my problem

So basically I had the problem that for my memory image either the DTB was not correctly determined or that the identity paging property did not hold true. Of course I also considered that the profile I built was incorrect and rebuilt it, making sure I was using the matching System.map and dwarf file, but to no avail.

I acquired another memory dump and let the system up and running, retrieving the virtual address shift by comparing the addresses in System.map with those in /proc/kallsyms and tried passing that shift to Volatility with the according option. But again: no luck. I then turned of KASLR by passing the nokaslr kernel option on the command line, and was pleased that with the memory acquired afterwards Volatility would play just fine (though at that time only with images in LiME format and not in raw format, but this was an [issue][lime-timeout] during acquisition as I later found out).

I concluded that my profile was just fine, and that I must be missing something else. After digging through the kernel change log, Kees Cook’s blog and LWN I finally found the issue: The KASLR shift for PAs and VAs was no longer identical.

Take this gif as a gift which gives an overview of KASLR evolution: